Vinyl as New Media

Historians often find themselves going back and back and back. Many a recovering graduate student can relate: a story that seemed to begin at one moment in time inevitably has roots that branch and stretch ever deeper into the past. A dissertation on consumer credit in the 1930s somehow becomes a thesis on the Panic of 1893, and before you know it, you’re writing about monetary policy in the British colonies.

So it was when I started writing about music piracy and copyright law over a decade ago. Clearly, the story of piracy did not begin with Napster and digital file-sharing in 1999, but with the rise of magnetic tape in the 1970s. There, the origins of our contemporary dilemma over technology, sharing, and property rights would be found. I soon learned, though, that Philips released the compact cassette in 1963, and magnetic recording in its various forms—four-track, reel-to-reel, wire—had a history reaching back to the late nineteenth century.

But what was far more surprising was that copying and sharing were not native to the cassette era at all. The recordability and erasability of tape seemed fundamental to the business of illicit music—the essence of piracy, bootlegging, counterfeiting, or however you want to describe unauthorized reproduction of sound. Yet people had been pirating music since the dawn of recording itself. Somehow, jazzheads in the 1930s, opera buffs in the 1950s, and rock radicals in the late 1960s found a way to duplicate a seemingly solid and fixed medium—the disc record.

How was this possible? Vinyl seemed to be the essence of an analog medium. It possesses none of the qualities of “new media” as defined by theorist Lev Manovich: numerical representation, modularity, automation, variability, and transcoding.[1] A turntable had no record button, and an LP was neither searchable nor easily subject to remix or rearrangement.

While tape does not quite match Manovich’s definition of new media—which essentially means digital media—it did have qualities that presaged an era of copying, sharing, and near-effortless recombination. As William Burroughs discovered in his 1967 essay “The Invisible Generation,” the compact cassette was a subversive little box. Sound could now be recorded at the push of a button, secretly and covertly, and then cut, spliced, or otherwise manipulated. It could be recorded, rewound, and mass-reproduced with a few tape decks and a little determination.

Yet it was not really magnetic tape that touched off America’s first great skirmishes between piracy and copyright in the twentieth century. For example, in one extraordinary episode in the early 1950s, the major labels made a big show of their determination to stamp out the piracy that had proliferated since the end of World War II. “Now there is a babel of labels,” record collector Frederic Ramsey Jr. observed in the Saturday Review in 1950, surveying a scene thick with shady and elusive outfits that bootlegged old jazz and blues recordings in the new medium of vinyl. A Victor spokesman vowed in 1951 to “seek injunctions and damages, prosecute, throw into jail and put out of business” the lawless competitors who flagrantly copied their records, many long out-of-print, without permission.

Victor, then, was deeply chagrined to learn in November that one of the most brazen bootleggers—the indiscreetly-named Jolly Roger—had been pirating records in the label’s own facilities. Using a custom-pressing service that was meant to produce limited batches of records for small businesses and community groups, the jazz enthusiast Dante Bollettino had produced reissues of Jelly Roll Morton, Cripple Clarence Lofton, and other artists at Victor’s plants—making the label an accomplice in its own defrauding. Bollettino insisted that he was simply making music available that the major labels refused to keep in print; the market, they said, was simply too small to warrant committing scarce resources of advertising, production, and shelf space to such obscure records.

In retrospect, Victor in 1951 looks like the epitome of what scholars call a “Fordist” enterprise: a company that maximized profits by committing its factories and sales staff to selling as many copies of as few records as possible. The early 1950s was the heyday of a few major labels and a few big radio and television networks. The vast multiplicity and variety of contemporary media was far off in the distance, if visible at all, at mid-century. But a handful of renegades like Bollettino still found a way to turn the infrastructure of the industry against itself, to press vinyl records of out-of-print music for a niche audience in runs of 300 or 500 discs.

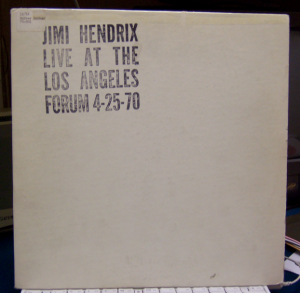

Vinyl became the vehicle of piracy again in the late 1960s. A massive bootlegging craze was touched off by the surreptitious release of Bob Dylan’s “basement tapes” in 1969, but few listeners experienced the music in the medium of magnetic tape. In fact, the radical bootleggers who exploded on to the scene at the close of the decade, vowing to free music from corporate control, did so primarily on vinyl LPs. With the subsequent leak of unreleased Beatles tracks (which circulated in San Francisco several months before Let It Be was released) and live performances by Jimi Hendrix, Neil Young and numerous others, a rich material culture of bootleg vinyl spread around the United States and the world in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Records appeared with titles like Stealin’ and Kum Back (a joke on “Get Back”), as different assortments of the same unauthorized and unreleased recordings appeared under countless names by a panoply of “labels,” some of which put each record out under a different business name.

Consider Dylan’s basement tapes. Variously called Great White Wonder, Little White Wonder, and Troubled Troubadour, depending on the countercultural scamp who made them, these recordings all appeared on vinyl, manufactured at independent pressing plants that had proliferated since the 1950s, as the major labels lost their grip on the means of production. One of the most notorious of 1960s pirates, Rubber Dubber, operated a facility in East Los Angeles—all while sending his bootlegs to Rolling Stone to review, giving interviews to Harper’s Weekly, and dodging probes by the RIAA and the police.

(In one comical episode, Dubber misled investigators hired by David Crosby to track down the notorious bootlegger; the detectives showed up at a house in Kansas and served papers to an angry and harassed homeowner at four in the morning—who turned out to be the local sheriff of police.)

Aficionados of jazz, blues, and classical music had quietly copied and shared records for decades, but the eruption of rock bootlegging in the late 1960s prompted the first major reckoning with piracy and copyright since 1909, when Congress amended the Copyright Act to deal with the challenges of an age of wax cylinders and piano rolls. Lawmakers at that time declined to give labels or artists a right to own their recordings; only written music could be copyrighted, and recorded sound lacked protection in the United States for another 62 years. Rubber Dubber and his brash fellow pirates helped provoke a lethargic and uncertain Congress to pass the Sound Recording Act of 1971, which created the first American copyright for the recorded performance as a distinct work.

Thus began a period of unrelenting expansion of copyright that continues to this day—terms of copyright protection grew longer, penalties for infringement became dramatically stiffer, and the scope of intellectual property itself expanded to include many “works,” such as biological life, that were not ownable prior to the late twentieth century.

But piracy in the late 1960s did not just prompt a rethinking of intellectual property law; it also reminds us that social, political, and cultural upheavals do not derive purely from technological change. Yes, magnetic recording likely made it easier for the Beatles’ and Dylan’s “tapes” to leak out of the studio, but as most listeners experienced these seminal bootlegs, they were still inscribed in the medium of vinyl—despite the technological and institutional barriers that stood in the way of illicitly reproducing disc records.

Vinyl, in its strange way, was a kind of transitional technology: the midwife between a twentieth-century model of mass production and a contemporary culture of mass reproduction typified by cassettes, “burnt” CDs, and MP3s. Vinyl itself is a more flexible medium that one might expect—at least when it’s placed in ingenious human hands. After all, Kool Herc figured out how to chop up, mix, and loop recorded sound using two turntables in the early 1970s, pioneering the quintessential music of postmodern pastiche—hip-hop—without the help of tapes or digital samplers.

In everyday use, boundaries between technologies are often much less clear than they appear. Dylan’s basement tapes were actually LPs, in the same way that many hip-hop “mixtapes” were actually CDs and now can be downloaded as MP3s. Das Racist’s Shut Up, Dude is still a mixtape, even if no magnetic particles or ferric oxide intervened. The dawn of free culture began with vinyl, even if it seems like an unlikely candidate for opening the way to a file-sharing revolution.

[1] Lev Manovich, The Language of New Media (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2001), 27-48.

Comments are Closed